Introduction

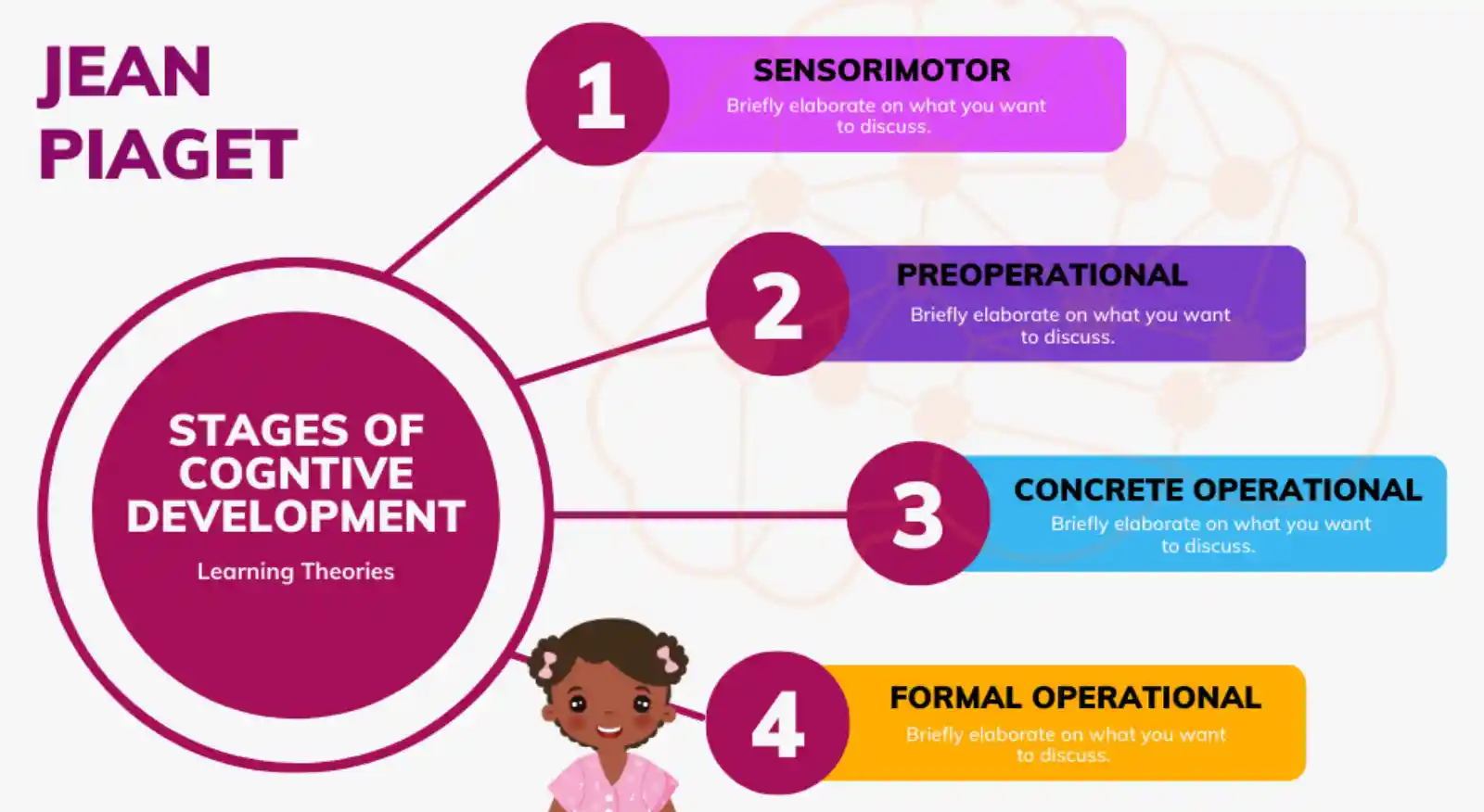

Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development explains how children grow and learn by interacting with their environment. His framework is widely used in education and psychology to understand how thinking evolves from infancy to adulthood.

Piaget divided cognitive development into four stages, each representing different ways children process information and develop reasoning skills. In this article, we’ll explore each stage and how it shapes learning.

1. Sensorimotor Stage (Birth to 2 Years) – Learning Through Senses and Actions

At this stage, infants explore the world using their senses and physical movements. They learn by touching, grasping, looking, and listening.

Key Characteristics:

- Development of object permanence – understanding that objects exist even when out of sight

- Learning through trial and error

- Beginning of intentional actions, such as shaking a rattle for sound

Example:

A baby enjoys playing peekaboo because they don’t yet understand that the person is still there when hidden. As they grow, they realize objects and people continue to exist even when unseen.

How Parents Can Help:

- Provide sensory toys like rattles, textured books, and mirrors

- Encourage exploration in a safe environment

- Play interactive games like peekaboo

2. Preoperational Stage (2 to 7 Years) – Imagination and Symbolic Thinking

Children at this stage start using words, images, and symbols to represent objects and experiences. However, their thinking is still intuitive and egocentric.

Key Characteristics:

- Development of language skills

- Engaging in pretend play (e.g., playing house, talking to stuffed animals)

- Difficulty understanding other perspectives (egocentrism)

- Struggles with logical reasoning

Example:

A child might think the moon follows them when they walk outside, as they don’t yet understand distance and perspective.

How Parents and Teachers Can Help:

- Encourage storytelling, drawing, and imaginative play

- Ask open-ended questions to stimulate thinking

- Use simple explanations for concepts like sharing and fairness

3. Concrete Operational Stage (7 to 11 Years) – Logical Thinking Develops

At this stage, children start understanding logic, cause-and-effect relationships, and conservation (the idea that quantity remains the same even if its shape changes).

Key Characteristics:

- Development of logical thinking

- Ability to understand conservation (e.g., the same amount of water in different-sized cups)

- Less egocentric thinking – they can see others’ viewpoints

- Improved classification and organization skills

Example:

If you pour the same amount of water into a tall glass and a wide bowl, a child in this stage will understand that the amount of water hasn’t changed.

How Parents and Teachers Can Help:

- Provide hands-on learning experiences, like measuring ingredients in cooking

- Encourage sorting and categorizing activities (e.g., grouping toys by color or size)

- Introduce simple problem-solving tasks

4. Formal Operational Stage (12 Years and Up) – Abstract Thinking and Reasoning

Teenagers and adults in this stage develop the ability to think abstractly, reason logically, and solve complex problems.

Key Characteristics:

- Ability to think hypothetically and understand abstract concepts

- Developing critical thinking and reasoning skills

- Understanding concepts like morality, justice, and ethics

- Forming personal identity and opinions

Example:

A teenager can understand philosophical questions, like “What would happen if there were no laws?” and discuss potential outcomes logically.

How Parents and Teachers Can Help:

- Encourage discussions about real-world issues and ethical dilemmas

- Support independent problem-solving and decision-making

- Provide opportunities for debates and structured arguments

Why Piaget’s Theory Matters

Understanding Piaget’s stages helps parents, educators, and caregivers create age-appropriate learning experiences. It highlights the importance of hands-on learning in early childhood, structured problem-solving in middle childhood, and abstract thinking in adolescence.